The Cadillac STS-V (2006-2009) uses the 4.4L supercharged Northstar engine, making 469 hp and 439 ft-lb of torque. Can it make more?

Cadillac used a modified variant of the Magnuson MP122, or Eaton M122 supercharger, with a integrated intercooler using Laminova cores. The powerplant was designed specifically to be supercharged. The stock LC3 V8 uses 12 psi, or pounds per square inch, of supercharging. In other words, if atmospheric pressure is 14.7 psi, then air flooding into the LC3 at maximum pressure is 14.7 + 12 psi = 26.7 psi. In supercharger terms, it is at 26.7 / 14.7 = 1.82 pressure ratio.

As a rule, 1 psi of supercharging makes 4% more horsepower. Technically, 14.7 psi of supercharging would make 100% more power, or 6% per PSI. But, with inefficiencies, 4% per PSI is an achievable thumbrule. Looking at this backwards, one might find that a non-supercharged 4.4L V8 would have made 316 hp. This is very close to the 320 hp rating of the 4.6L VVT DOHC normally aspirated Northstar; no surprise.

So what would happen if we increase the boost level on the LC3 V8 from 12 psi up to say 14 psi or 17 psi? Notionally, in a perfect world the 469 hp stock would increase to 492 hp at 14 psi, or to 530 hp at 17 psi. However, there are issues to be considered such as the capability of the supercharger to make that much pressure efficiently, as well as the capability of the intercooler to take away additional heat produced.

A popular way to increase the output pressure of a supercharger is to substitute a smaller pulley for one or the other end or both ends of the supercharger pulley drive. For the STS-V LC3, the crank pulley appears to be 5.88″ outer diameter, and the supercharger snout pulley is 2.8″ outer diameter. Actually, I know the snout pulley diameter of 2.8″, and Cadillac said that the ratio between the two was 2.1:1. Also, when D3 created a 10% overdrive pulley, they chose to make it 6.47″ outer diameter, which is 10% more than 5.88″. This strikes me as an odd outer diameter, but note 5.9″ = 15 cm, so perhaps the crank pulley is metric?

Another choice is to change the supercharger snout pulley from 2.8″ to 2.55″. Remember our ratio — crank:snout pulley ratio so 5.88:2.8 stock = 2.1:1

If we change the crank pulley to 6.47″, then the pulley ratio changes to 6.47 :2.8 = 2.3. Now 2.3/2.1 = 1.1, or 10% faster, so 10% more boost, or 1.2 psi increase.

Likewise, a 2.55″ snout pulley would be 5.88:2.55 = 2.3 and 2.3/2.1 = 1.1 or 10% faster, so 10% more boost, or 1.2 psi increase.

Either way, 1.2 psi increase for 1.2 * 0.04 /psi = .048 or 4.8% increase. So a 13 psi LC3 might increase from 469 hp at the crank to 491 hp at the crank or 24 hp.

In an ideal world then, another PSI of boost would also add another 24 hp. For example, if we used a 6.47″ crank and 2.55 supercharger snout pulley for 6.47:2.55 = 2.5:1 ratio we could get to 2.537/2.1= 1.21 or 21% increase or 2.52 PSI. This would theoretically gain 47 hp and get from 469 to 516 hp.

A different approach is taken with the Stiegemeier Snake Bite kit. By modifying the internal gearing on the supercharger, and porting and cleaning up the flow paths within the supercharger, up to 17 PSI of boost is produced with the stock/OEM supercharger snout pulley and crank pulley. Theoretically this would gain 5PSI * 4%/PSI = 20% or 93 hp, boosting the LC3 from 469 to 563 hp. However, again with real world inefficiencies the actual gain would be expected to be less. I don’t see a claimed/measured gain on their website for this application.

So how do people get up to figures like 461 whp (wheel hp, or hp at the wheels on a dyno) or 576 crank hp (hp at the crankshaft on an engine test dyno) for the STS-V LC3? Through a careful combination of a variety of modifications.

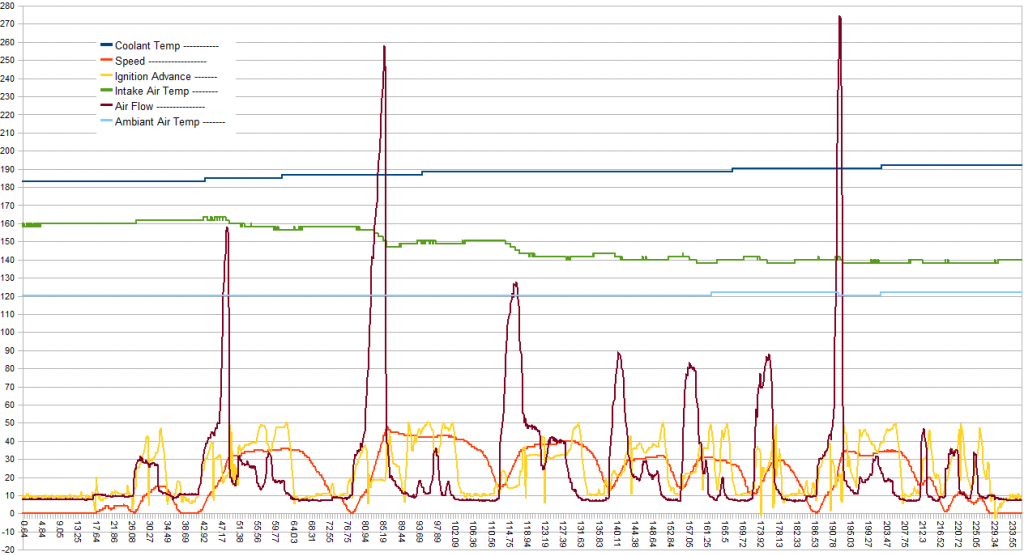

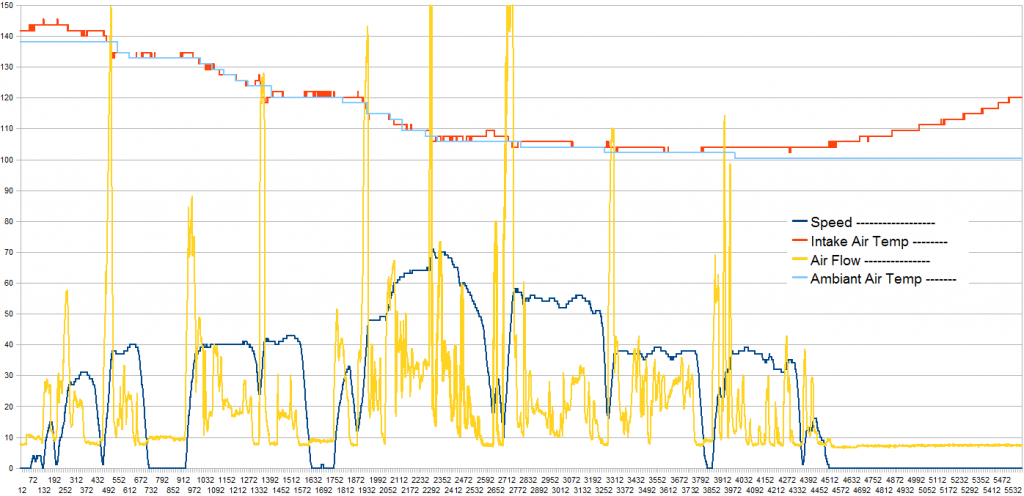

The actual boost the engine pulls has to overcome the intake resistance. So add a higher flow intake and the engine effectively has more boost as a result. Add more intercooler cooling and the engine can make and sustain more power. Tune the engine for a specific car and environment and the engine can make more power. Through careful tuning and multiple dyno runs the community and Professional Tuners have slowly pulled higher levels of performance from the LC3.

With the CTS-V release and adoption of the LSA supercharged 6.2L V8, there is less market for LC3 tuning and the focus has shifted to the newer cars. That does not change the inherent goodness and balance of the 4.4L Supercharged LC3 engines, and I am having a great time considering and researching tuning approaches for mine.

HEY!

See anything you disagree with? Did I get it ALL wrong? Do you agree and want to share your experiences? Put a comment up and join the conversation!